Mauryan empire in ancient india, full details

Key Points

- The Mauryan Empire, founded around 322 BCE by Chandragupta Maurya, was a significant pan-Indian empire covering most of the Indian subcontinent, excluding the southern tip.

- It seems likely that Chandragupta expanded the empire with help from Kautilya (Chanakya), defeating the Nanda dynasty and later Seleucus I Nicator.

- Research suggests Ashoka, reigning from 268 to 232 BCE, expanded it further but embraced Buddhism after the Kalinga War, promoting non-violence and cultural influence.

- The empire had a centralized administration, state-controlled sectors like mining, and a complex bureaucracy, with tradespeople organized into guilds.

- The evidence leans toward the empire declining after Ashoka due to weak successors and internal strife, ending in 185 BCE with Brihadratha’s assassination.

Foundation and Expansion

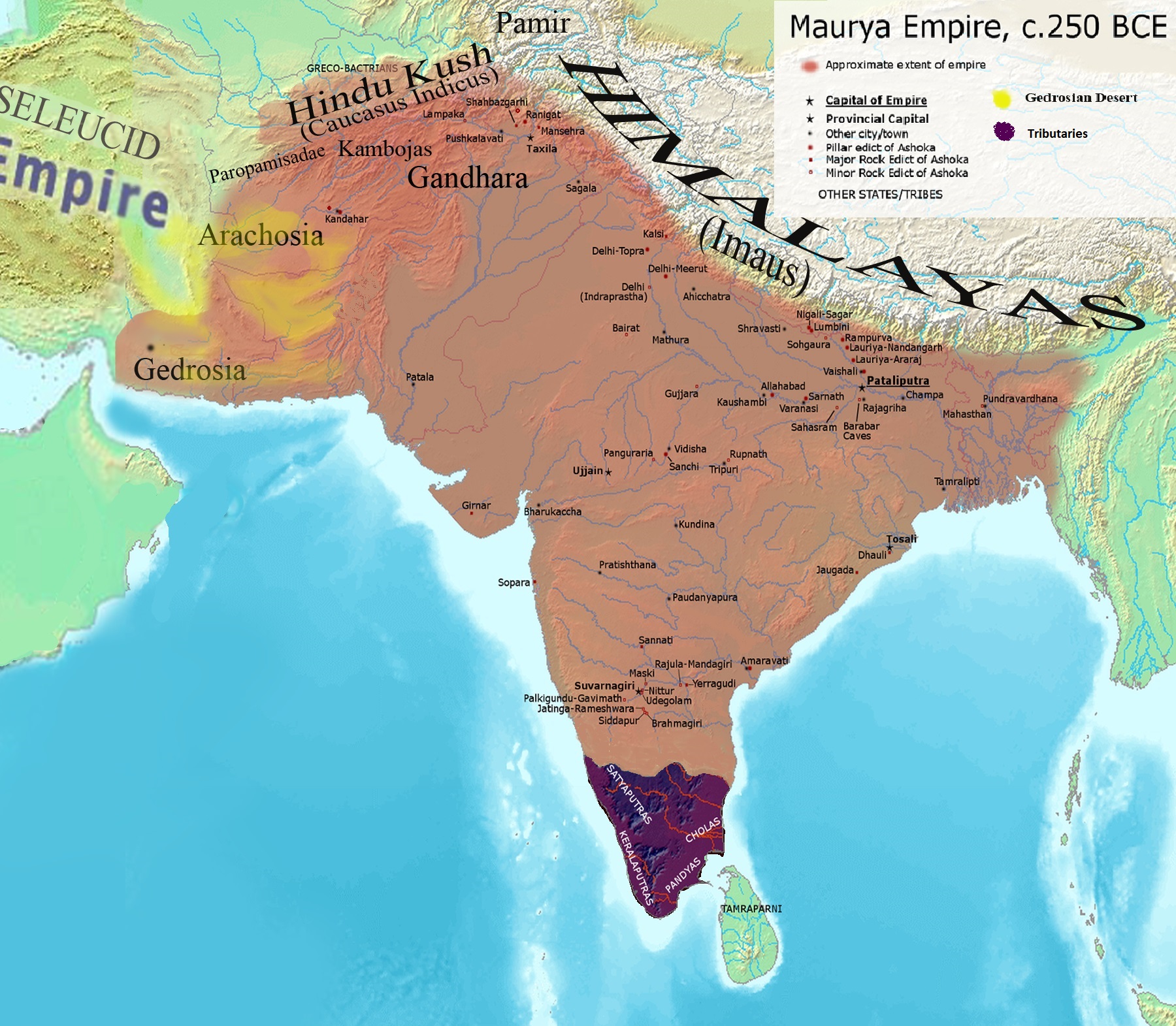

The Mauryan Empire began around 322 BCE when Chandragupta Maurya overthrew the Nanda dynasty, taking advantage of the power vacuum left after Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE. With the guidance of Kautilya (Chanakya), author of the Arthashastra, Chandragupta expanded the empire to include regions from eastern Iran to the Burmese hills and from the Himalayan tribal kingdoms to the southern plateaus. He ruled for 25 years before abdicating in favor of his son Bindusara and becoming a Jain monk.

Bindusara, reigning from 298 to 272 BCE, maintained and extended the empire’s southern borders to cover the peninsular plateau of India. His son Ashoka, from 268 to 232 BCE, further expanded it by conquering Kalinga in 261 BCE, but the war’s brutality led him to embrace Buddhism, promoting non-violence and sending evangelical missions abroad, including his son and daughter.

Administration and Economy

The Mauryan Empire featured a centralized administration with a complex bureaucracy, state control over key sectors like mining, salt production, and arms manufacture, and taxation on agriculture. Tradespeople were organized into guilds with executive, judicial, and banking functions, supporting a robust economy.

Decline and Legacy

After Ashoka’s death, the empire faced weak successors, internal strife, and border states asserting independence, leading to its decline. The last ruler, Brihadratha, was assassinated in 185 BCE by Pushyamitra Shunga, who founded the Shunga dynasty, marking the empire’s end. Ashoka’s promotion of Buddhism and animal protection edicts had a lasting cultural and religious impact.

Survey Note: Comprehensive History of the Mauryan Empire

The Mauryan Empire, a pivotal entity in ancient Indian history, was founded around 322 BCE by Chandragupta Maurya and lasted until 185 BCE. This survey note provides a detailed examination of its foundation, expansion, administration, cultural impact, and decline, drawing from multiple historical sources to ensure a comprehensive overview.

Historical Context and Foundation

The Mauryan Empire emerged in the wake of Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE, which left a power vacuum in the Indian subcontinent. Chandragupta Maurya, with the strategic guidance of Kautilya (Chanakya), author of the Arthashastra, overthrew the Nanda dynasty, establishing the Maurya dynasty. This period, dated from c. 320 BCE to 185 BCE, marked the beginning of a geographically extensive Iron Age power based in Magadha, with its capital at Pataliputra (near modern Patna).

Chandragupta’s early conquests included the Punjab region, and by the end of his reign, he had expanded the empire to cover regions from eastern Iran to the Burmese hills and from the Himalayan tribal kingdoms to the southern plateaus. A notable diplomatic achievement was his defeat of Seleucus I Nicator around 305–303 BCE, gaining territory, a daughter, and financial support, and establishing Megasthenes as a Greek ambassador. Chandragupta ruled for 25 years before abdicating in favor of his son Bindusara and becoming a Jain monk, reflecting the empire’s early religious diversity.

Expansion Under Successors

Bindusara, reigning from 298 to 272 BCE, maintained the empire’s northern and eastern extents while extending its southern borders to cover the peninsular plateau of India, stopping around modern Karnataka. His reign, lasting 28 years according to the Mahavamsa, saw the empire’s consolidation, with estimates suggesting a population of 15–30 million in the 3rd century BCE and a peak area of 3,400,000–5,000,000 km² by 250 BCE.

Ashoka, reigning from 268 to 232 BCE, is one of the most famous Mauryan emperors. He seized the throne after a fratricidal dispute and expanded the empire by conquering Kalinga in 261 BCE, a war that resulted in significant bloodshed, leading him to embrace Buddhism. His reign marked the empire’s height, with core regions including Taxila, Ujjain, Kalinga, Suvarnagiri (modern Karnataka), and the heartland around Pataliputra. Ashoka’s edicts, inscribed on pillars and rocks along trade routes, promoted non-violence, moral authority, and Buddhism’s spread, with missions sent to regions like Syria, Egypt, and Macedonia, though with limited success.

Administration and Economic Structure

The Mauryan administration was highly organized, modeled on the ideals outlined in Kautilya’s Arthashastra, which detailed administrative functions and state policies. It was a centralized autocracy with a standing army and civil service, lacking the technology to deeply penetrate society outside Magadha but efficient within its core. The capital, Pataliputra, was a hub of governance, with provinces ruled by princes (Kumar) assisted by Mahamatyas, and a decentralized structure in peripheral areas.

Economically, the empire featured public-private trade, with the state owning timber, forest land, hunting groves, manufacturing facilities, and maintaining monopolies over coinage, mining, salt production, arms manufacture, and boat building. Agriculture was taxed, and tradespeople were organized into guilds with executive, judicial, and banking functions, fostering economic development. Trade routes like the uttarāpatha, linking eastern Afghanistan to Patna, were used in winter (October–April) for trade, reflecting the empire’s integration into broader economic networks.

Cultural and Religious Impact

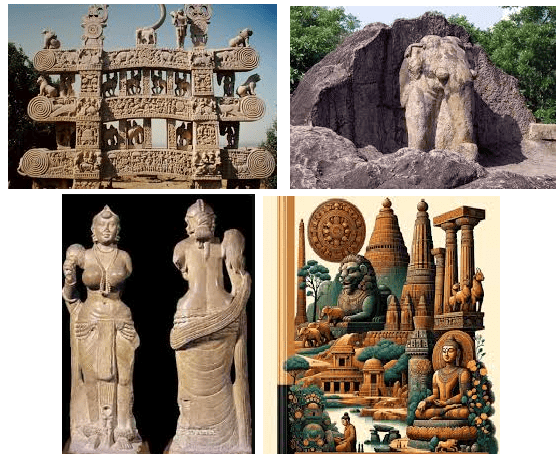

The Mauryan period saw significant cultural and religious transformations. Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism, often likened to Constantine the Great’s acceptance of Christianity, had a profound impact. He banned Vedic animal sacrifices in his capital, promoting compassion for animals, and issued detailed edicts protecting various species, such as parrots, bats, and tortoises, on specific days like Caturmasis and Tisa. These edicts, inscribed on rocks and polished sandstone pillars (e.g., the 32-foot-high pillar at Lauriya Nandagarh, Bihar, capped by a seated lion), are among the oldest deciphered original texts of India.

Brahmanism reinvented itself under Mauryan rule, transforming into a socio-political ideology across South and Southeast Asia. Ashoka’s patronage of Buddhism, including building 84,000 stupas to enshrine Buddha’s relics, and sending religious envoys, facilitated the religion’s spread, leaving a lasting legacy in Asian cultural history.

Decline and Legacy

The empire’s decline began after Ashoka’s death in 232 BCE, attributed to weak successors, internal strife, and border states asserting independence. The Puranas list subsequent rulers like Dasharatha (232–224 BCE), Samprati (224–215 BCE), and others, with the last ruler, Brihadratha, assassinated in 185 BCE by his commander-in-chief Pushyamitra Shunga, who founded the Shunga dynasty. By this time, the empire had shrunk to Pataliputra, Ayodhya, Vidisha, and parts of Punjab, a fraction of its former size.

The decline was marked by invasions, defections by southern princes, and quarrels over ascension, with scholars citing the empire’s vast size and weak post-Ashoka rulers as major reasons. Despite its fall, the Mauryan Empire’s legacy endured through Ashoka’s edicts, the spread of Buddhism, and its administrative model, influencing subsequent Indian and Asian political systems.

Detailed Timeline and Rulers

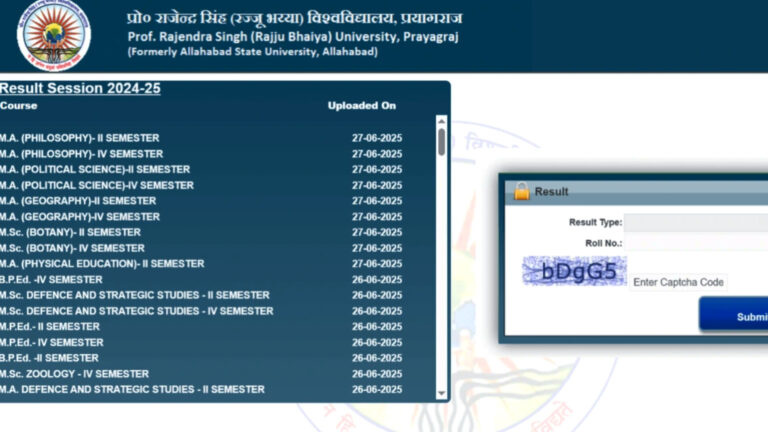

For clarity, the following table summarizes the key rulers and their reigns, based on historical records:

| Ruler | Reign Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chandragupta | ca. 322–298 BCE | Founded empire, defeated Nanda and Seleucid, abdicated as Jain monk. |

| Bindusara | 298–272 BCE | Extended to southern India, ruled 28 years, died c. 273 BCE. |

| Ashoka | 268–232 BCE | Peak of empire, Kalinga War, embraced Buddhism, died 232 BCE. |

| Dasharatha | 232–224 BCE | Ashoka’s grandson, succeeded him. |

| Samprati | 224–215 BCE | Reconquered lost territories. |

| Shalishuka | 215–202 BCE | – |

| Devavarman | 202–195 BCE | – |

| Shatadhanvan | 195–187 BCE | – |

| Brihadratha | 187–185 BCE | Last emperor, assassinated by Pushyamitra Shunga in 185 BCE. |

This table, derived from sources like Wikipedia and Britannica, highlights the dynastic succession and key events, providing a structured view of the empire’s timeline.

Sources and Archaeological Evidence

Primary sources for Mauryan history include partial records of Megasthenes’ lost Indica, preserved in Roman texts, the Edicts of Ashoka deciphered in 1838 by James Prinsep, and the Arthashastra, now dated to the 1st centuries CE with composite authorship. Archaeologically, the period falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), with Ashoka’s pillars and stupas as enduring relics, such as those in Panjim, Goa, India.

In conclusion, the Mauryan Empire’s history, from its foundation by Chandragupta to its decline under Brihadratha, reflects a complex interplay of military conquest, administrative innovation, and cultural transformation, leaving a lasting legacy in Indian and global history.